Communication and politics: the impossibility of separating them

The horizon shifts when we think of politics as the sphere and practice of collective life in which the meanings of social order are designed and discussed.

- Opinión

| Article published in ALAI’s magazine No. 513, 514: La comunicación en disputa 02/06/2016 |

Some fifteen years ago, one of the most lucid Argentine intellectuals, Sergio Caletti, pointed out that one of the difficulties for thinking critically about the links and crossovers between communicational and political phenomena was the very nature of these links, added to the persistence of an “ultimately technical conception of communication and politics”[1]; that is to say, the identification of communication with strategies of production and dissemination of messages and of politics with a social apparatus or mechanism, that is, a regulated institutional framework.

In spite of the complexification that has taken place since then, this way of thinking of communication and politics continues to predominate today. This persistence is reflected in the many productions that question the way in which communication – in terms of technology and strategies – affects politics in terms of an institutionalized activity. Thus, many studies blame the media and technologies for the deterioration of politics that is turned into a spectacle or entertainment or, on the antipodes, there are those that promote democratic and participative advances thanks to networks and interactivity.

It is not possible to overcome these restrictive and dichotomous perspectives if one operates with instrumental concepts of communication and politics. The horizon shifts, on the other hand, when in addition to taking into account the institutional dimensions of politics – its organizations, its moments of deliberation and decision –, we think of it as the sphere and practice of collective life in which the meanings of social order are designed and discussed, that is to say the principles, values and norms that regulate communal life and future projects. And it changes when, without denying its operative dimensions, we think of communication as those complex interchanges through which individuals and social groups produce meanings in permanent tension and confrontation. It is this kind of notion that underpins the sixth thesis of that text of Caletti, which holds that communication constitutes the condition of politics in a double sense: because one cannot think of political action as a discussion of ideas without actors who discuss, and because one cannot think of this practice in terms of building future projects without the collectivization of interests and proposals.

This particular and necessary linkage between communication and politics is produced today in a public space constituted as much through what I have called “the plaza”, that is to say the traditional spaces of collective gathering and action – spaces that acquire new forms as time passes – and the “stalls”, that is to say the media practices that are sustained on our condition as media audiences and users of information and communication technologies[2]. This mediated public space is one of the principal areas where the struggles for political power, for the leadership of society, are determined, struggles that are not independent from communicative-cultural power, that is to say, the possibility of constructing hegemonic ideas. A possibility in which there is decisive intervention of the technical devices that allow for the media appearance and representation of themes and actors. John Thomspon therefore proposes that “the struggle to make oneself be heard and seen (and to prevent others from doing the same) is not a peripheral aspect of social and political communication in the modern world; quite the contrary – says Thomspon – it is its central characteristic”[3].

In our Latin American societies, which in spite of their democratic institutions are characterized by notable inequality and exclusion, these struggles to be seen and heard, that are struggles against those who seek to prevent this, are hardly new. They find historical expression both in the resistance of native peoples and in the search for alternative cultures. Nevertheless, in this century, various countries in our continent have staged specific efforts to submit the systems of mass media and their legal regulation to discussion, transforming communication rights into one of the areas where the struggles for power are expressed most forcibly.

I can sustain this assertion in the confrontations that have taken place and are happening today in Argentina with respect to the Law of Audiovisual Communication Services, or those that have occurred and are occurring in other countries of the region, such as Ecuador or Uruguay, in a similar sense. In many cases these confrontations are connected to a long tradition of popular, alternative and community media, built from the necessity and vocation to recover the capacity and legitimacy of self-expression, both for excluded minorities and for majorities who lack the means of access to media and technology. In all these cases, it is possible to retrieve the discourse and practices that clearly identify antagonistic interests and their consequent ideological justifications: that is to say, competing interests that affirm or deny the universality of communication rights. And it is here that the connection communication-politics is revealed with unusual potency, undermining as never before those boastful notions of independence and objectivity of the media that are part of our mass communication systems.

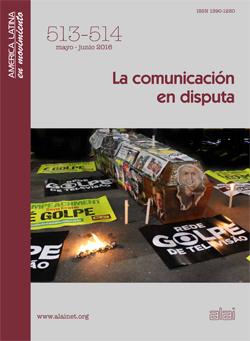

Beyond the particular characteristics of each of our countries, the existence of monopolies or oligopolies -- that, far from diminishing, are growing with the processes of technological development and convergence -- produces well-known effects: single-track agendas, concentrated voices, insufficient spaces for the expression and representation of different social and political actors and sectors. Moreover, these media companies that seek to hoard for themselves the communication rights that belong to the whole of society, no longer even try to hide their motivations and strategies in the struggles for power. They openly intervene as a political actor, proposing ideas or projects, calling for participation or abstinence, denouncing or covering up political or business figures, promoting or stigmatizing candidates, pronouncing their judgement on social movements when they confront the established order and judging even justice herself, even though– in many of our countries – she is not precisely the equable blindfolded dame, but yet another instrument for the construction of inequity. The cases of the multimedia Clarín conglomerate in the recent Argentine electoral process, or that of the Red Globo in the impeachment process in Brazil, are clear examples of this new role.

Nevertheless, I do not believe that it is adequate to affirm that politics is “done” today in the mass media, loading this doing with a negative or perverse content. Historically, political constructions had interactive dimensions and turned to means of expression. Politics was always practical and discursive action. What is happening today is that transformations have taken place that it is necessary to understand in order to act without complacency but also without nostalgia. On the one hand, as I have already pointed out, the fact is that the media corporations, practically without mediation, without veils, have assumed an undeniable participation in the construction of formal and exclusionary democracies. But on the other hand, it is also a fact that political institutions – I am thinking of parties, State powers, electoral campaigns and processes – have been transformed in the framework of what has become known as a “demoscopic democracy”[1], a democratic order where media public opinion and the techniques of measurement and prediction of social behavior acquire a decisive weight in strategic and tactical definitions.

The critical questioning of this new political-cultural matrix is not the same as denying it. There is nothing worse than voluntarist attitudes when one aims to intervene in conflicts for hegemony. Therefore, recognizing that the communications system is one more actor in the struggles for power in our societies, we must venture to address this situation from two complementary and mutually necessary places: from the search for regulations that lessen media concentration and ensure more equitable conditions for media management and access to adequate technologies for a plurality of different social actors; and from the development of organizational and political practices that, without denying the existence of media and technologies, define renewed ways of installing themes, agendas, leaders, projects, from an associative and cultural logic capable of confronting the guidelines pre-established by those who aim to control emancipating initiatives.

At present, this is not simply a question of being able to develop alternative media in order for other voices to be heard and other faces seen, but also to assume that one of the new and decisive battles is that of collectively defining what we desire to be the political-cultural order of our societies. Assuredly there is no new political order without a new way of communicating, but it is not only a renewed way of communicating that will enable us to construct democracies with full rights and genuine modalities of participation and representation.

(Translated for ALAI by Jordan Bishop)

María Cristina Mata is a researcher and lecturer in communication at the National University of Córdoba, Argentina. She accompanies media and communication projects of popular and alternative communication in the continent.

Article first published in Spanish in ALAI’s magazine América Latina en Movimiento No. 513-514, May-June 2016, http://www.alainet.org/es/revistas/513-514

[1] “Siete tesis sobre comunicación y política”, en Diálogos de la Comunicación N° 63 (37-49). FELAFACS, Lima, 2001

[2] Nociones desarrolladas en “Entre la plaza y la platea”, en Schmucler H. y Mata,M. (Coord.), Política y comunicación. ¿Hay un lugar para la política en la cultura mediática? (pp. 61-76). Catálogos- UNC, Buenos Aires, 1995

[3] Los media y la modernidad, p. 398, Paidós, Barcelona, 1998.

Del mismo autor

Clasificado en

Comunicación

- Jorge Majfud 29/03/2022

- Sergio Ferrari 21/03/2022

- Sergio Ferrari 21/03/2022

- Vijay Prashad 03/03/2022

- Anish R M 02/02/2022